Repairing Broken Handrail Gate Latch

Sanderling is a Defever 41 built in 1987 with lots of teak – window frames, hand rails (with three gates), cap rail, topside trim and seats, and deck. We’re willing to put in the extra work that is required to enjoy the warm appearance of the teak. Our former trawler had the same type of bright-work and we knew how to deal with it. One thing we hadn’t dealt with before was a broken gate latch.

Sanderling’s three gate latches consist of two similar stainless steel parts: one with a sliding pin fixed to the gate, and the other, with an L-shaped piece with a hole which the sliding pin engages, attached to the stationary hand rail. The “broken” gate latch prevented the swinging end of the gate on the starboard side from fastening securely. This is our most used gate since we always try to saddle up to a dock on the starboard side due to left-hand engine rotation. I considered it a safety hazard, particularly when underway, since a slight amount of upward force on the gate would cause it to open. When the gate latch “broke” part way through this past summer’s cruise, I didn’t want to take a chance that dismantling the latch might result in loss of the gate completely, so I didn’t attempt repairs until we reached our home marina this fall. We just had to be extremely careful when traversing the side decks near the broken gate.

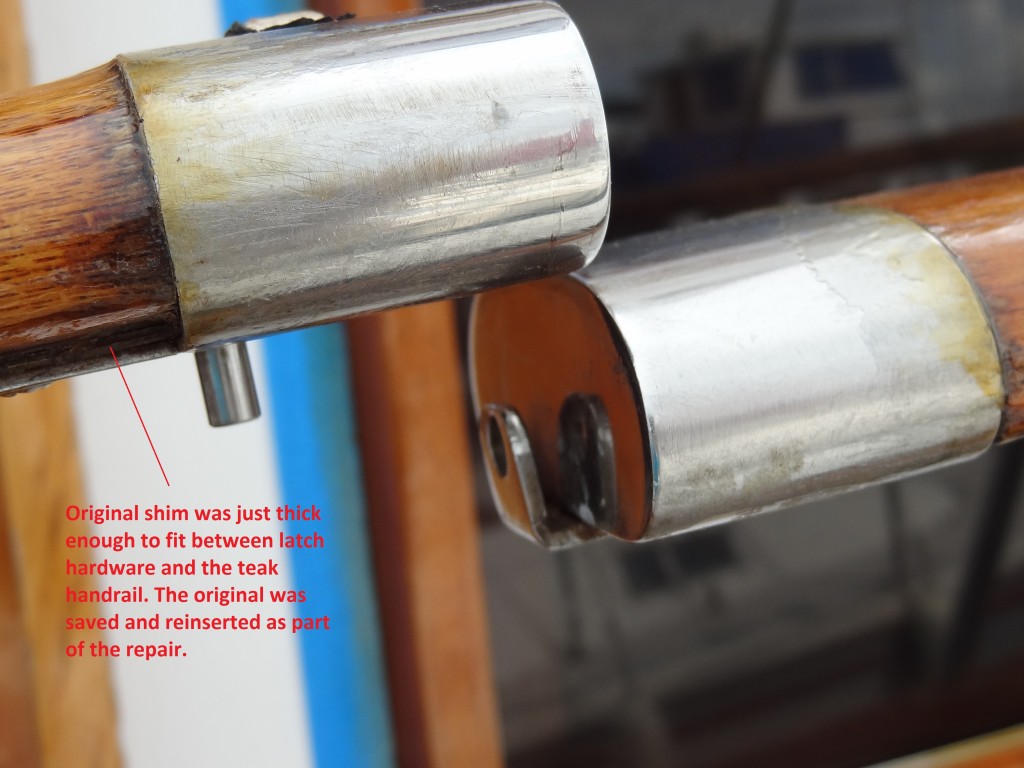

The first photo shows how the gate latch parts (the stationary part on the rail and the part on the gate itself) go together as the gate closes. The photo also shows the location of the shim that is inserted between the tang on the latch and the gate, and the L-shaped piece with the hole that engages the pin and holds the gate securely. This type of latching mechanism seems to be common on trawlers with teak hand rails.

The latch slides over the end of the gate and is fastened with five screws from the bottom. The first concern was whether removal of the hardware would require the use of heat and as a consequence damage the underlying teak. Once I removed the screws and started gently tapping the edge above the teak rail with a small hammer and large flat-blade screw driver, the latch moved slowly with each tap, but was obviously fit quite snugly on the rail. Fortunately, no heat was required even though there may have been some caulk or adhesive used when it was originally put in place. There was also the need to hold the gate as firmly as possible so as not to damage the hinge part of the gate mechanism, and to hang onto the latch so as not to have it fall overboard if it suddenly came loose and jumped out of my hand!

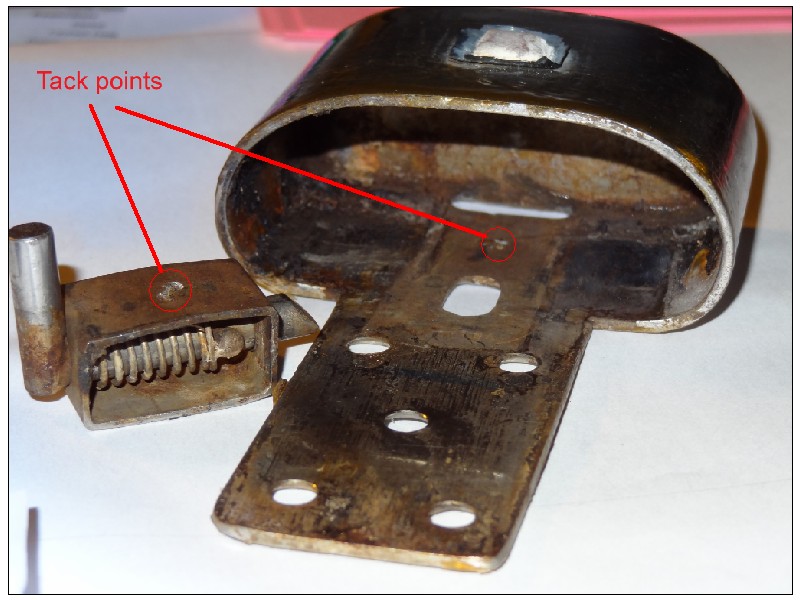

Once it was successfully removed, the problem became apparent. The small 4-sided box that holds the movable pin and spring assembly had come unfastened from the main frame of the latch.

The second photo shows the box with spring and pin (turned upside down from it’s normal position) and the apparent single-weld attachment point with the corresponding attachment point visible inside the stainless latch frame. The beveled end of the pin engages the hole in the corresponding fixed latch, while the upright portion of the pin extends below the latch and is moved back with a finger to disengage the pin from the hole. The spring holds the pin in it’s closed position.

The third photo shows the end of the gate with the latch removed. You can see the hollow area where the spring box is located and how the teak has been slightly reduced to accommodate the thickness of the latch frame.

It seemed that a tack weld on either side of the spring box would be the ideal solution, but I couldn’t find any shop that would do the two tack welds for a reasonable price. Consequently, I used a “puddle” of JB Weld to fasten the spring box to the frame after smoothing out the two mating surfaces and removing the remnants of the original tack.

The fourth photo shows the latch back together with a bit of JB Weld showing around the edges of the spring box.

Hopefully, JB Weld will hold the two parts together; if not, I’ll write another article about how to get the parts welded together.